The Art of Bioethical Resilience in the Midst of Grief and Fear

January 19th is the anniversary of the liberation of the Lodz ghetto and this page is adapted from a Grand Rounds presentation given on January 19, 2022. I’ve been giving Grand Rounds on or around that day for many years as one way of remembering.

Art can empower resilience in the midst of loss, grief, danger, and fear. Like putting art in the context of its age or era, we have to put pandemic grief in a context of time: the beginning in Feb-March 2020, 6 months in, and January 2022 nearly two years in.

How has the COVID pandemic evolved from its beginnings?

- Health-care inequities causing higher death rates among the poor and people of color

- Greater awareness of intermediate and long-term effects of COVID

- Widespread vaccine hesitancy highlighting problems when people who are terrified, depressed, and demoralized consider benefits vs. risks

- Staff demoralization from exhausting case overload, the tragedy all around them, and their limited ability to help their patients; even now clinicians face more severe demoralization when patients expect help while being unwilling to help themselves

- People are divided rather than united in community: kids vs. seniors vs. other adults; those with kids vs. without kids; those vaccinated vs. not; those masked vs. not

- Survivor guilt and shame in survivors of those who have perished

- Identification with the aggressor on the part of some who are living with unvaccinated people and who may either get vaccinated and feel guilty or not get vaccinated and be more vulnerable than they otherwise would be

- Bad normalization: cumulative addiction to anxiety and despondency in the general population, with manifestations that include carelessness and desire to normalize with or without a reasonable basis to do so

- Good normalization: with vaccines plus a variant that has less serious consequences for most people who get it, we’re living with COVID rather than dying with it

Problems people have with decision making in such stressful, frightening, demoralizing conditions:

- Hyperfocus on risks and discounting of benefits

- Focus on shorter-term and neglect of longer-term outcomes

- Focus on a tree and lose sight of the forest

- Rigidity: with grief and fear and demoralization, people have a more difficult time changing their minds, the “freeze” of the “fight, flight, or freeze” response

- Making everything be about self-esteem & self-righteousness: People who resist vaccines and masks try to shame those who take those precautions and those who resist usually are the self-righteous ones

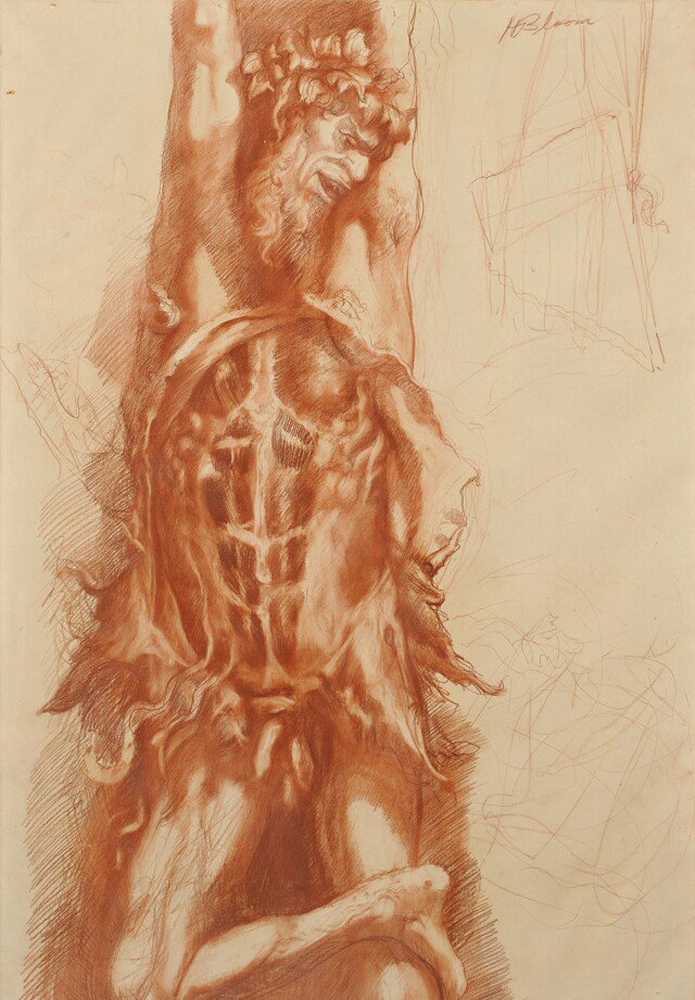

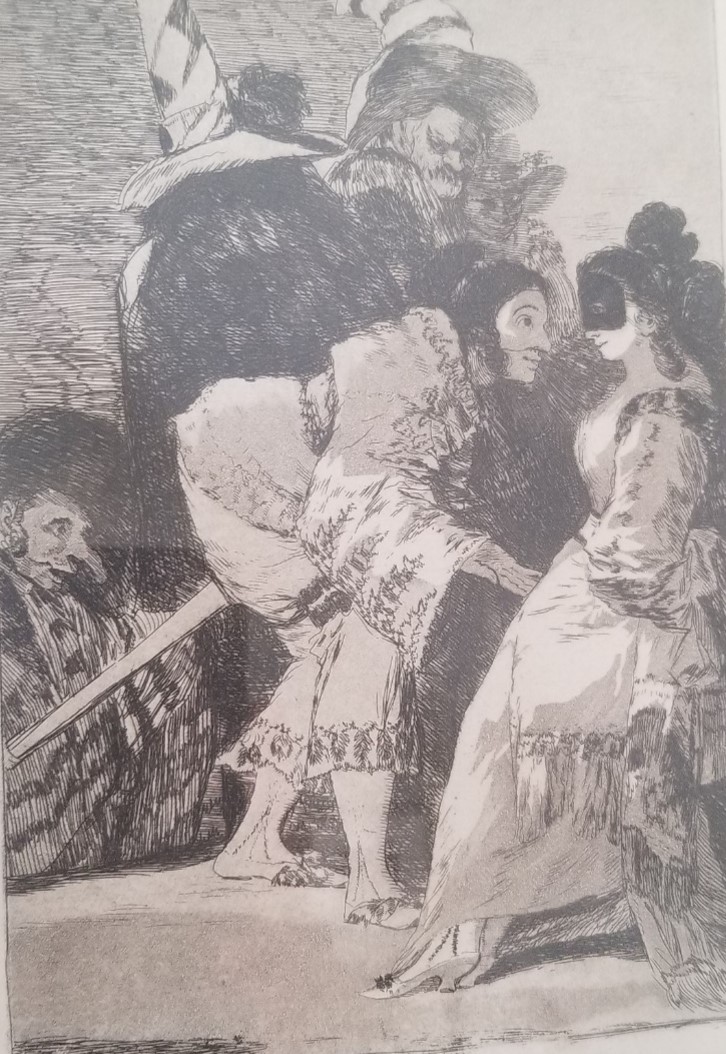

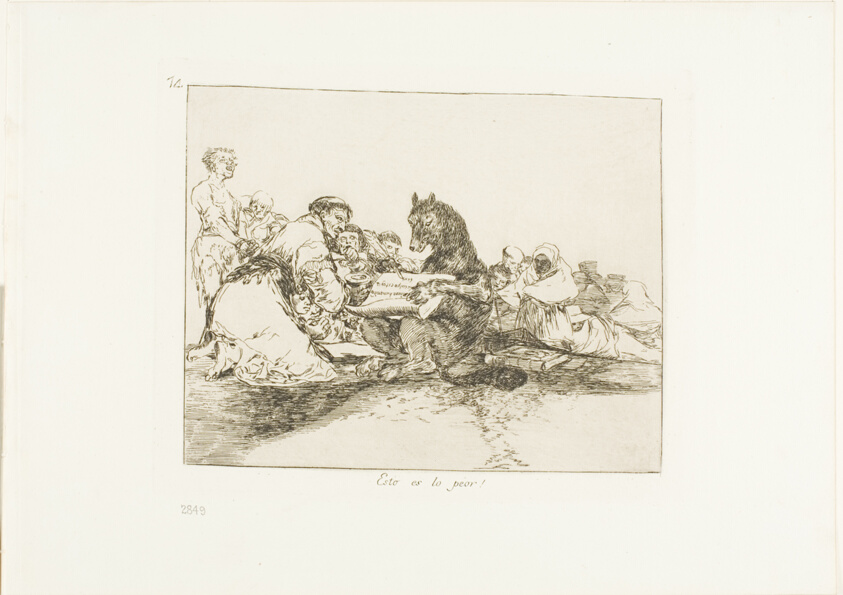

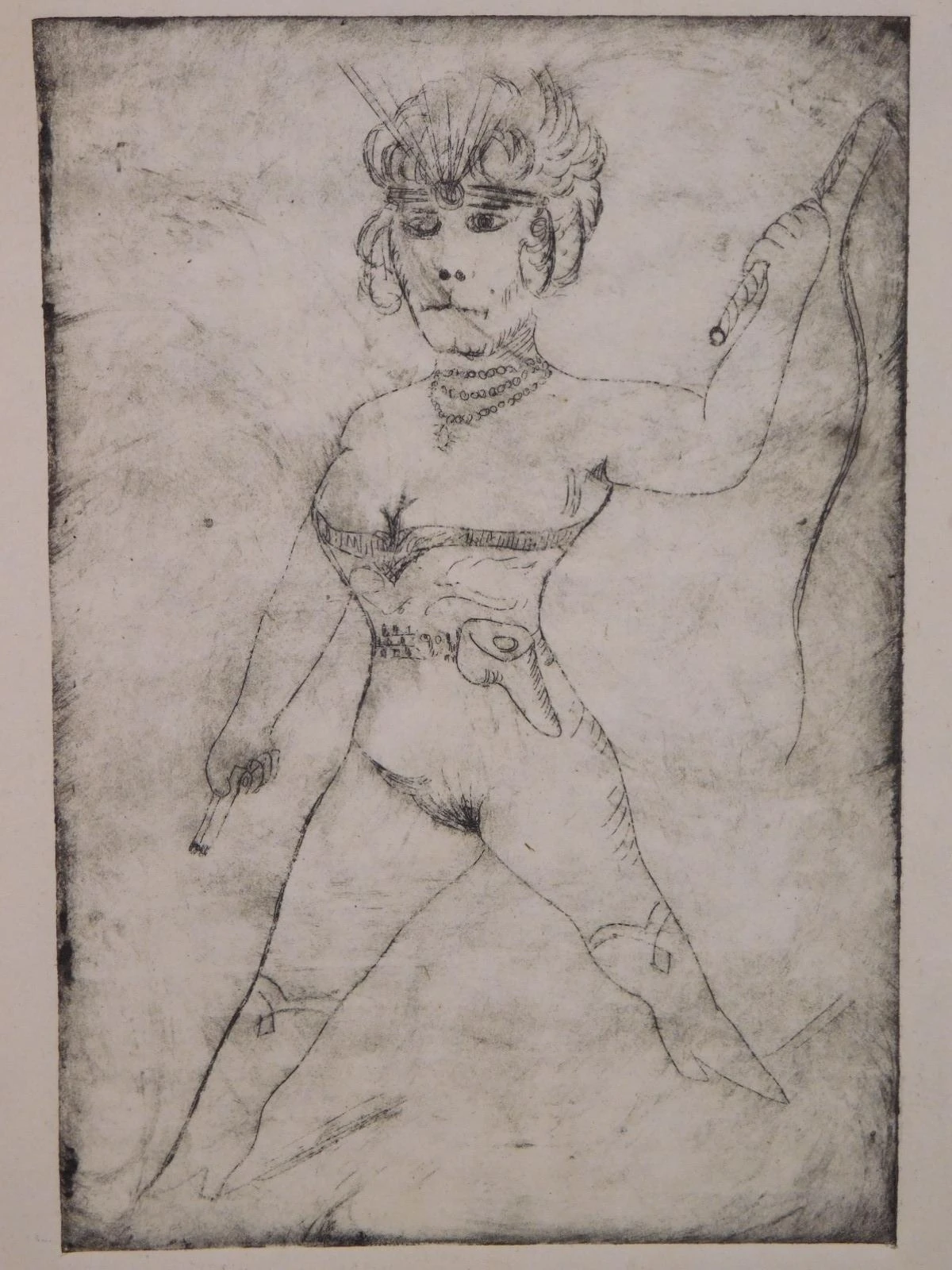

How art can help us address the effects and ravages of time and the grief it brings:

- Visual art is not atemporal. Responses to art change over time in two ways: (1) the distance in time (up to centuries) and space (cultures) between the creator and the viewer or listener (we respond to Vermeer differently from a Dutch person of his time); (2) the length of time a person knows a work of art, from first impression to later reexperience and reconsideration, as affected by one’s growth in years and experience and by one’s relationship with the work. Being able to look at the same thing twice and have a different reaction reminds us that we can change our minds.

- Music, which is built on and proceeds though time (tempo and rhythm (both Melodic and Harmonic)), also gives us a way to address the effects of time and thereby helps us think about consequences of actions.

- Why is time, as we experience it through art (visual, verbal, musical, dramatic) important? It gives us representations of how we experience time in life.

Examples:

In a jail in a small community where the prisoners were gang members and the guards were ex-gang-members, I was asked to interview a prisoner in a corner of the cafeteria, separated from the other prisoners with guards watching. Suddenly the guards disappeared for suspicious reasons. A prisoner from the opposing gang approached. The one I was interviewing told me, “That guy’s got a shank. He’s going to try to shank me.” Trying to save him, and my own skin as well, I asked the one who was menacing us, “What time is it?” He looked at his watch, told me the time, and walked away. I did that instinctively, but it conveyed a deeper meaning. Orienting the would-be assailant to time normalized the situation—reminded him that actions have consequences in time (in his case, a longer prison sentence). If you don’t keep track of time, especially in demoralized environments, there are consequences.

Vaccine deniers who cry “fascism” are talking concretely, with no distinction between what’s similar and what’s different, whereas music plays with similarities and differences across time. This can be explored with patients in terms of the music they like. Art in any form can provide context for talking about issues that come up. Try to go where the patient is, what they respond to, to help them move away from concrete thinking by introducing a time dimension, similarities and differences, without lecturing.

Clinical Applications: Empowering Patients and Building Alliances in the Face of COVID Helplessness and Fear

How to respond to the added threat COVID poses for patients with different conditions, some of whom are already vulnerable from loss and grief, as well as overburdened health-care workers dealing with traumatized patients.

In my home office I currently see patients both virtually and in person. All my in-person pts are fully vaccinated and boostered, as I am. An air filter is installed, and I maintain physical distance between myself and the patient.

Case 1: Highly intelligent, imaginative professional woman in complex grief who requires testing, health precautions, and switch to virtual meeting when her maskless dentist tests positive a day after seeing her

This is a highly intelligent professional woman in complex grief (her beloved brother died tragically, and she now lives alone) whom I see in person. Recently she texted me that the day after she saw her dentist, the dentist tested positive for COVID and was not wearing a mask.

I replied by thanking her for keeping in contact and recommended the following:

- Daily temperature checks

- Inform her primary-care physician

- Keep well hydrated

- Arrange to get tested in 3 days

- Feel free to keep in contact with me

I followed up to explore how this threat of COVID might relate to her underlying grief. She noted her disappointment with him and her desire to see another dentist and I noted to her that if I ever act anywhere near that thoughtlessly to please let me know.

A response such as this opens the way to a more collaborative relationship with the patient. It acknowledges that I’m not perfect, that I’m not trying to achieve perfection (some patients, especially teenagers, can’t distinguish between striving for excellence and for perfection). Discussing this kind of issue in this way can help build an alliance.

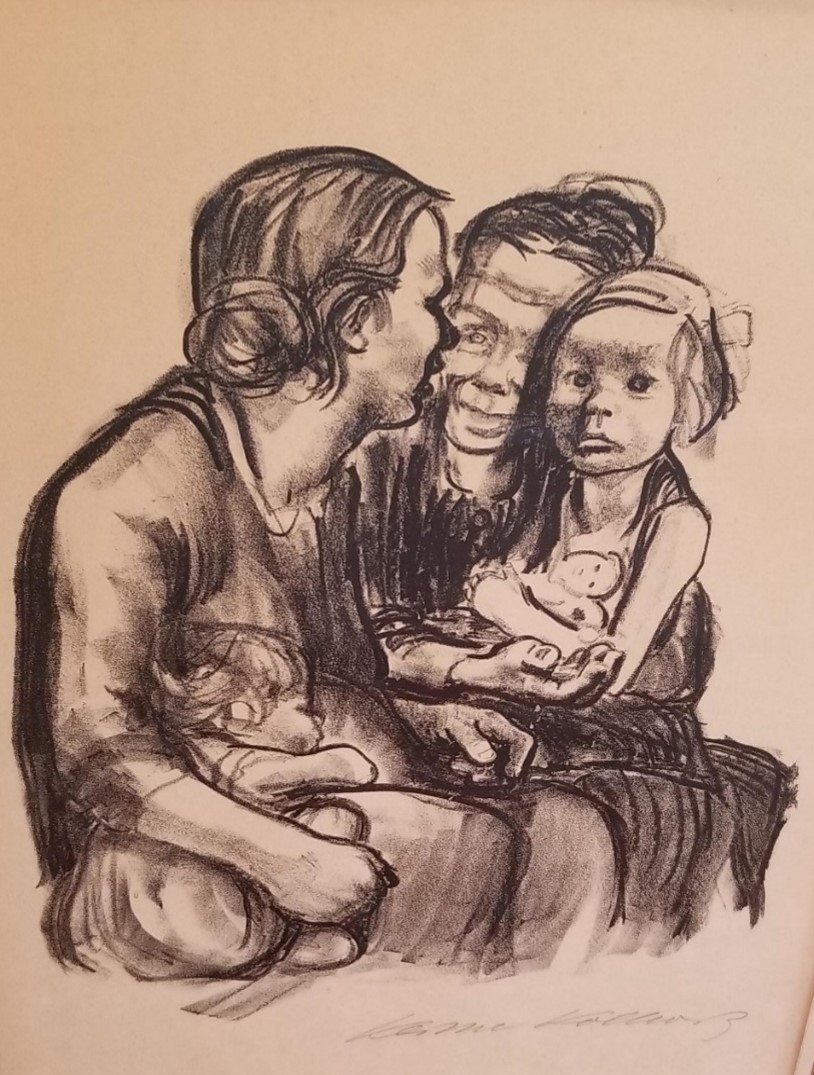

Case 2: Widowed child survivor of the Shoah for whom imposed isolation in her home brings back early memories of isolation and hiding

This woman is a child survivor of the Shoah who lives alone, her husband having died before the pandemic from Alzheimer’s disease. I meet with her on Zoom. For her, the isolation at home imposed by the pandemic brings back memories of isolation and hiding in the Shoah. This background affects current choices she faces, such as whether to visit her son, whose sister-in-law and niece, coming from Alaska to see him, may not be fully vaccinated.

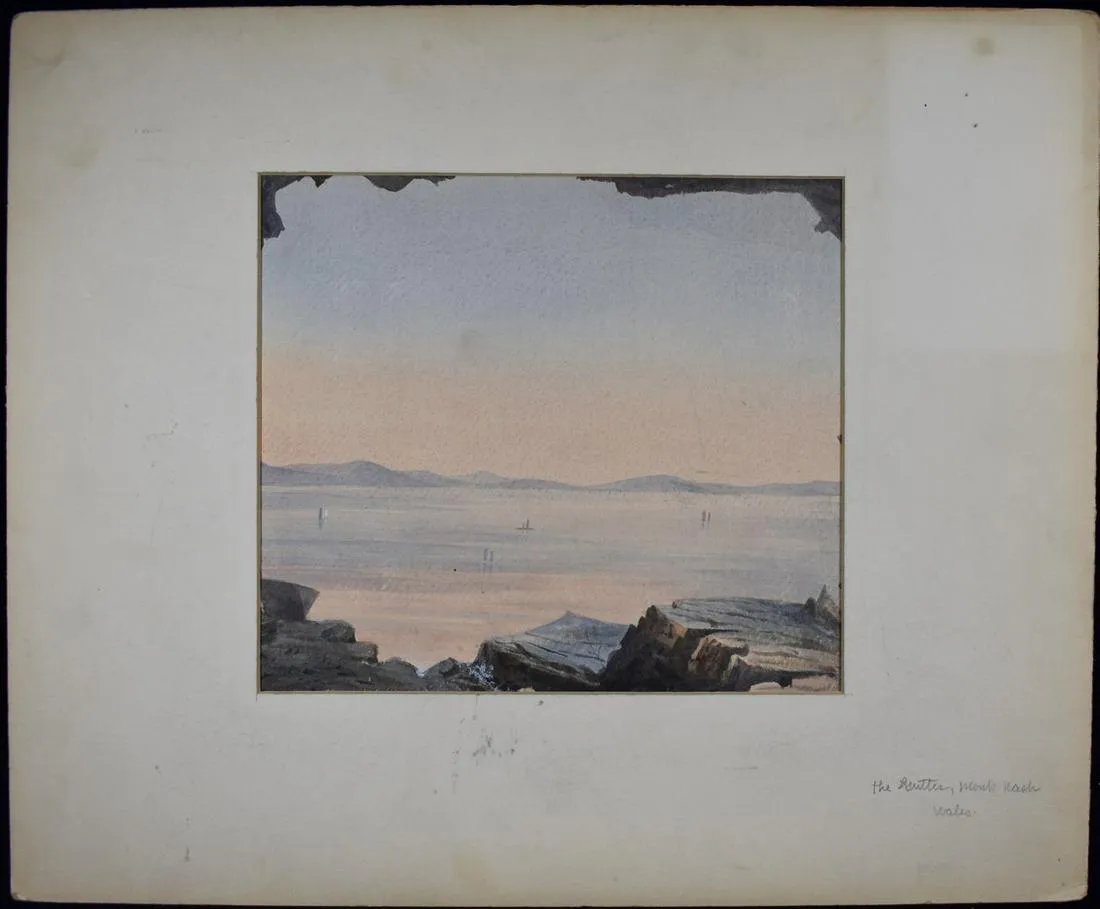

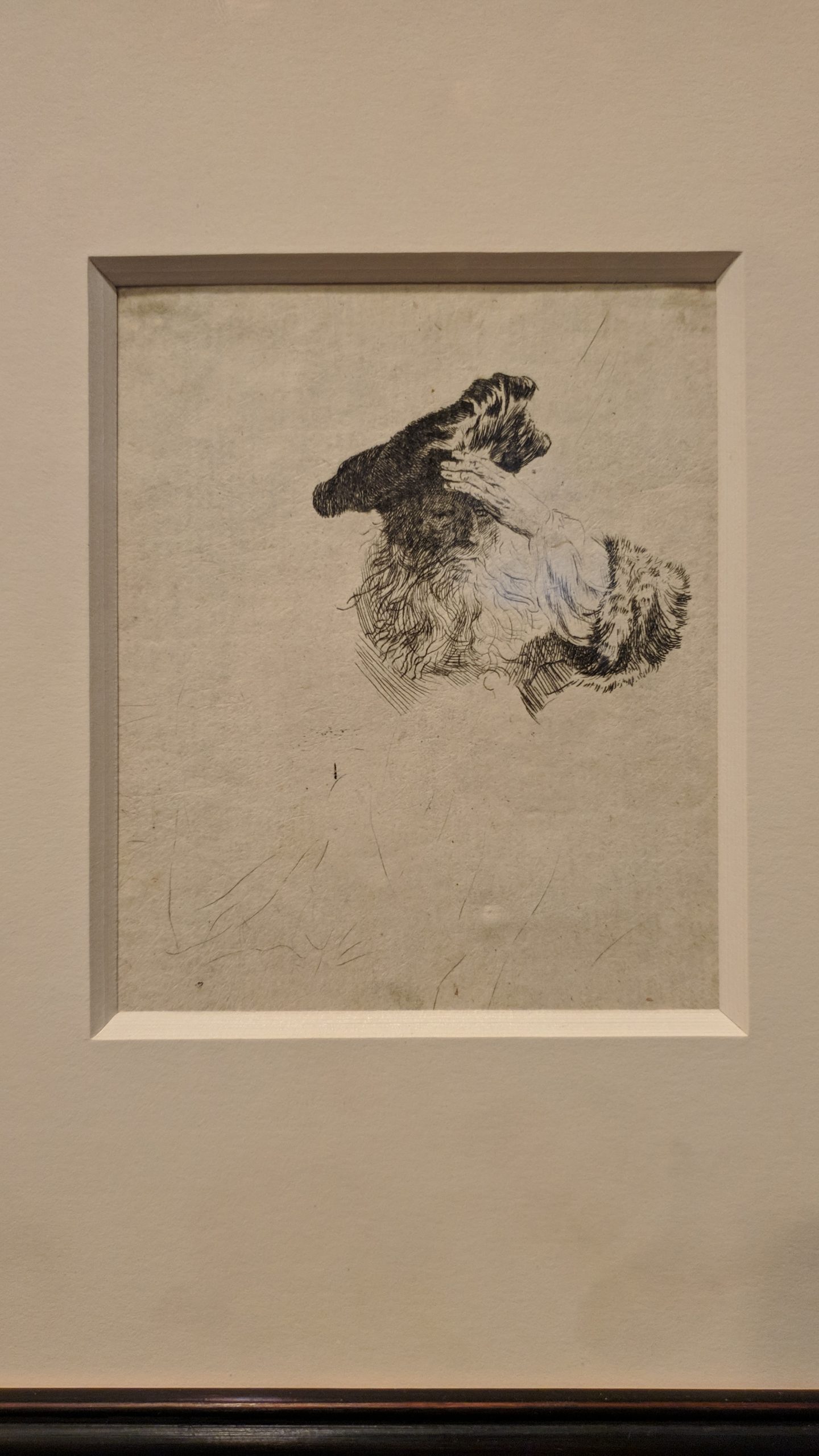

These days she says she likes seeing on her screen the painting on the office wall behind me which reminds her of being here in my office. She looks forward to being able to be with me in person once again. For now, she feels it’s “not the same” since she can’t shake my hand when she left my office. We analyzed that.

These days she says she likes seeing on her screen the painting on the office wall behind me which reminds her of being here in my office. She looks forward to being able to be with me in person once again. For now, she feels it’s “not the same” since she can’t shake my hand when she left my office. We analyzed that.

Case 3: Teenage boy, who recently started college, deciding whether to tell his anti-vaccination parents that he is getting vaccinations and booster

A teenage boy who recently started college away from home but still goes home to visit his parents between school sessions. His parents are nice people who are dead set against vaccination. Their having suffered serious losses in the last few years, with feelings of helplessness engendering a short-term focus, may account in part for their vaccine avoidance. I have explored with this young man his dilemma of whether or not to tell his parents that he is getting vaccinated and boostered. It’s a case example of the complications of human agency. Would it help or hurt all concerned, and their relationship, for them to know that he’s getting vaccinated and to make it a family issue? We are working to resolve this conflict by moving from unconscious guilt—feeling that he’s a coward to hide that he is vaccinated or humiliating his parents if he tells them—to a consideration of the real choices he faces and their potential consequences. If he chooses not to disclose, it is not something shameful; rather, he has a right to privacy, and he can choose to spare them added stress given all that they’re already facing. If he does tell them and they get upset, he is not doing it to humiliate them, but out of a desire to have an open and honest relationship, as well as concern for them. Either way, he’s getting vaccinated as much to protect them, and others, as himself.

Case 4: Young man exploring how his girlfriend’s needing to isolate and be tested when she flies to China and back may affect their relationship, and what that means about the relationship

A young man whose girlfriend will be flying to China and back. We are exploring in detail how her needing to be tested and to isolate may affect their relationship. Here the exigencies of COVID provide an occasion for deeper exploration of a relationship.

Case 5: Rescheduling a session in a way that provides opportunity for a teenager with two very powerful parents to experience dignity and agency

The intrusion of COVID, which necessitates rescheduling, can provide an opportunity to build a therapeutic alliance in the midst of change, entropy, fear and to support dignity and agency on the part of a young person with two very powerful parents by involving him in decision making.

Just as with an adult patient such as the one in Case 1, it’s good to offer a couple of times and let them choose, so that they won’t feel so helpless. When you have some latitude, you can ask, “Will that be convenient for you?” When you don’t have much latitude, you can ask, “Can you make this work?”

Case 6: Workplace bullying—“You work or you die”: A vulnerable worker in a health-care facility is pressured into tasks that bring her into closer contact with patients than her job description calls for

This is a potential employment-law issue, since it is not part of her job description to provide up-close patient services. However, staffing shortages in the pandemic bring about understandable improvising on the part of management to have “all hands on deck.” Nonetheless, someone with a health condition that puts her at high risk for COVID should be exempt from such tasks under ADA and OSHA.

A complicating factor is a family heritage that goes back to a time and place in history when conditions were so dire that refusing work was not an option. This may leave her feeling too intimidated to resist the added work demands.

Summary: Helping patients and health-care workers cope with COVID

These cases have shown how the COVID pandemic has had different meanings and impacts for people at different stages of the life cycle and also in relation to their individual life histories, circumstances, and relationships.

Bringing up the question of vaccination (and other needed precautions) with patients should be done in way that’s helpful and not humiliating, since it concerns how they are making choices that currently affect their well-being in significant ways, which in turn can open up other explorations. And, of course, for patients seen in person it’s necessary.

Having up-to-date vaccine mandates for health-care workers is necessary for health care to proceed. Otherwise, staffs will be divided in ways that make it untenable. We do not want to deny health care to people who are unvaccinated, but in their case special precautions must be taken. That is not punitive, but realistic in view of the risk to others.

In consulting to people working in health-care facilities, I see what it means to lose patients when staff or visiting family are unvaccinated or lie about their status, as well as the toll it takes on people who work with vulnerable people while wearing masks and face shields all day.

Whether talking with patients directly or advising clinicians on how best to talk with patients, it is helpful to be straightforward without being punitive, moving people away from the concrete to see the big picture. Analogies can be helpful, e.g.: When you don’t put on a seat belt, you’re putting others at risk, as drunk driving does. A flying body injures others, and the driver can lose control more easily when the driver is unbelted or is hit by an unbelted passenger. Just as dancing with a partner is not a solo act—you can’t step on their toes.

Whereas choices like getting vaccinated or wearing seat belts or masks (where called for) are straightforward, other risk assessments in daily life are less clearcut (how to weigh the relative risks of shopping at a supermarket, eating indoors or outdoors at a restaurant, going to church, seeing a doctor, attending a baseball or football game, riding on a bus or train, flying in an airplane, or walking through a crowded airport). We can’t estimate these risks with certainty nor should we dismiss them as unknowable. We want to help patients get past the extremes of denial of risk vs. doom-saying so they can use realistic judgment.

As with the examples I showed earlier, art can help us take different perspectives on the same facts, events, or circumstances. Talk with patients about what movies, books, music, pop culture they enjoy. For example, movies like Don’t Look Up, which laughs at itself as it dramatizes disastrous ways of responding to disaster, or Black Sea, in which denial in the face of grief leads to catastrophic grief for oneself and others as people end up self-destructing and turning on one another. In Kafka’s The Trial, when the painter explains to Joseph K that there are only two alternatives to conviction—apparent acquittal followed by rearrest or an endless pretrial limbo—one can see a reflection of Kafka’s living with a chronic illness, tuberculosis, and now, a century later, of the successive waves of this pandemic, the feeling and the reality that it’s never over. As much as possible, couch the conversation in terms of what speaks to the patient.